No, no, no, no, no - or yes

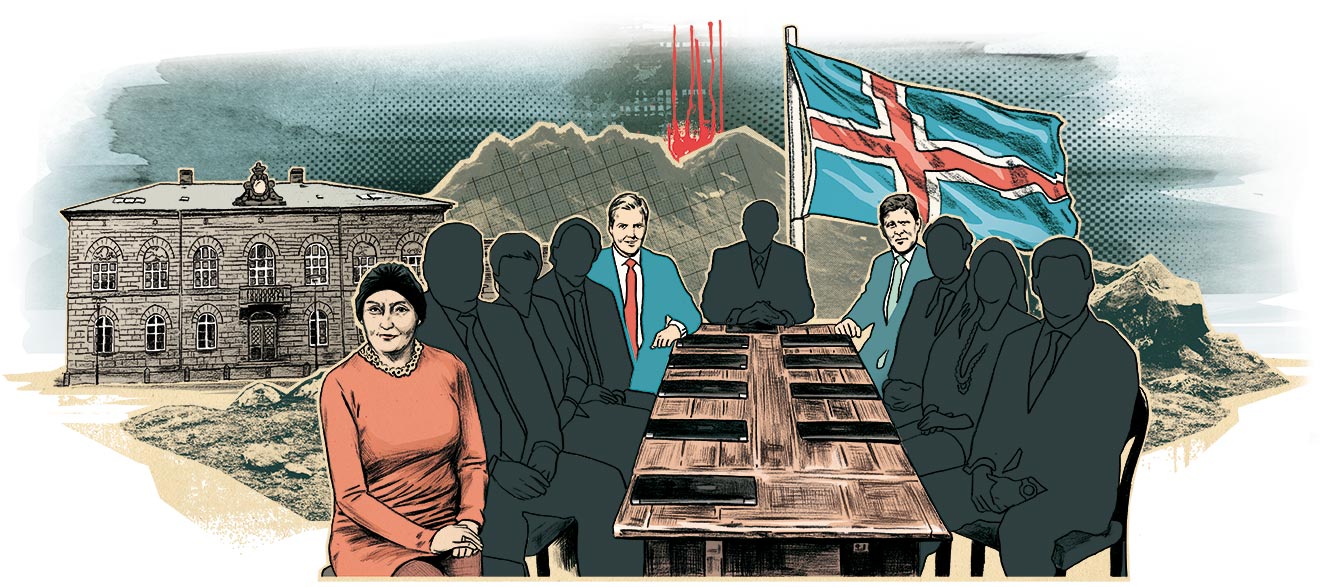

In the end, Sigmur Gunnlaugsson blamed everything on his wife. Iceland’s prime minister claimed that Wintris, the shell company, belonged to her, and not to him. But the tactic didn’t help: he had to resign anyway.

Olafur Grímsson, the president of Iceland, is now also facing allegations involving offshore business transactions. He, too, has asserted that these dealings are his wife’s financial affairs, and that he and the first lady lead “independent lives”.

The question is: will Icelanders believe him? Will they accept the claim that his wife was the sole beneficiary of several offshore companies – far more than the single company that forced the fallen prime minister to resign?

The first lady’s links to two offshore companies and five offshore accounts were first revealed in the Swiss Leaks data, which the Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Guardian first analyzed about a year ago. Now, in the wake of the Panama Papers revelations about Iceland’s political elite, they have taken another look.

The leaked documents were from the Swiss branch of HBSC. Dorritt Moussaieff, the president’s wife, appeared several times in the data.

Just two weeks ago, Grímsson announced he would be running for president again in a bid to extend to his 20-year tenure. After the Panama Papers had rocked the country, he claimed he wanted to restore stability.

“No, no, no, no, no. This will not be the case.“

Shortly after the president made his announcement, CNN invited the 72-year-old politician to an interview, during which star journalist Christiane Amanpour asked: “Do you have any offshore accounts?” She then followed up with: “Does your wife have any offshore accounts? Is there anything about you and your family that could be revealed?” The president answered: “No, no, no, no, no. This will not be the case.“The president repeated “no“ five times to CNN. And yet the family of Grímssons’s wife appears to have been linked, or may still be linked, to more than five offshore accounts.

Combined with the Panama Papers, the Swiss Leaks documents paint a clear picture. According to the data, the first lady’s family – and the first lady herself – made rampant use of offshore structures. Dorritt Moussaieff is the daughter of a very wealthy Israeli diamond dealer. Her name alone was linked to at least five Swiss HSBC accounts and two offshore companies. Around 2006/2007, her parents and two sisters ostensibly held as much as USD 80 million in HBSC accounts.

In itself, owning offshore companies and holding Swiss bank accounts is legal. However, the question remains as to how Iceland’s population will react to the latest revelations. Since the Panama Papers were published, the country has been in a period of political turmoil. There have already been six resignations: besides the prime minister, the chairman of the progressive party has also stepped down, for instance.

In recent weeks, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson has thus been a key figure. The president lives outside of Reykjavik in a picturesque white manor on the coast. During the chaotic week following the Panama Papers revelations, journalists drove to his house a number of times. However, their questions weren’t about the president, but rather about the prime minister, the finance minister, and the minister of the interior. They had come under fire because of shell companies, and the government plunged into crisis as a result.

In Iceland, the president has limited powers; he is not generally meant to be involved in everyday politics. This has never bothered, Grímsson, however, who has always managing to put himself in the spotlight.

And now his wife appears to be involved

The week the crisis started, he didn’t waste any time: he was present as early as Monday, the day after the program revealing the prime minister’s offshore company was broadcast. In Reykjavik’s government district, conversations revolved mainly around Grímsson, and how he was going to cut short his trip to the United States to rush home. On Tuesday, the president refused to give the prime minister permission to dissolve parliament, and this ultimately forced him to resign. On Wednesday, cabinet negotiations began, for which Grímsson gave his blessing on Thursday. That afternoon, he invited the three young Icelanders who organized the mass protests outside parliament to meet with him. He made headlines every day that week. And then, in the CNN interview, he explained that the mass protests were “in part the result of moral outrage“. And now his wife appears to be involved as well.Doritt Moussaieff married the president in 2003. She is his second wife. Grímssons’s first wife died of leukemia in 1998. Last week, SZ and Icelandic media revealed that the first lady’s parents owned an offshore company with Mossack Fonseca in Panama, via their diamond trading company in London.

Now, however, Doritt Moussaieff, too, appears to have had links to offshore companies at a time when she was already married to Grímsson and was first lady. In the HSBC data, Moussaieff and her sisters were listed as the beneficiaries of an offshore company called Jaywick Properties and the Moussaieff Sharon Trust. In addition to this, they were linked to a foundation called the Mrs S Levontin Trust, which held as much as USD 2 million in six accounts around 2006/2007. The trust appears to have been named after Moussaieff’s sister Sharon Levontin.

Moreover, as the Swiss Leaks documents showed, the first lady was also listed as a secondary beneficiary for two other companies: Easton Investments Inc. and Elyakeen Limited. The latter was with the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, just like her parents’ shell company. The law firm’s internal documents, the Panama Papers, show that the company held accounts not only at HSBC, but also at Deutsche Bank, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Mercury Bank Zürich. Another document refers to a loan of 13 million British pounds, which was to be taken up for tax reasons.

The president has issued the following statement about the revelations: “At no time has President Grímsson had any information about the financial affairs of his wife or any other members of the Moussaieff family.” Through a lawyer, the first lady has also stated that she and the president “keep their financial affairs separate”, and neither of them knows anything about the other’s finances. Moussaieff’s lawyer also stated that his client observed all tax and legal regulations.

Excessive hubris

But what will Grímsson do if his fellow Icelanders’ moral outrage is directed at him this time? He is said to be unpredictable. In recent years, he has announced his resignation twice. The first time was during his new year’s speech in 2012, but then he stayed because Icelanders had asked him to given the great “uncertainty” that followed the financial crisis. During his 2016 new year’s speech, he announced once again that he did not plan to run for another term. And then, two weeks ago, he changed his mind: he intends to run to help the country.The political science professor went into politics at an early age. He began as member of the liberal-conservative progressive party, which mainly represented the interests of farmers and fishermen. Grímsson was a member of the party executive before switching to the “Union of Liberals and Leftists”, a leftist splinter party that he ran for election with. It wasn’t until later that he made it into parliament with the People’s Alliance, a party with communist roots. Grímsson was a member of parliament for nine years, and was also Iceland’s minister of finance for a time.

Birgitta Jonsdottir, party leader for the Pirate Party, has stated that the spotlight-loving president suffers from “excessive hubris”. And Thorvaldur Gylfason, the head of the constitutional council, is responsible for drafting a new constitution that would not support Grímsson. In commenting on the president’s decision to run for another term, Gylfason stated: “The president is part of a political class that has done major damage to Iceland. Having a new president would be good for Iceland”.